‘Living With,’ was written as a foreword for Jonathan Orlek, Artist-Led Housing: Histories, Residencies, Spaces, (Leeds: East Street Arts, 2024).

This book has many beginnings. One of those is Jonathan Orlek’s doctoral thesis,[i] which documented the embedded ethnographic research that took place during his residency (in and out of) in East Street Art’s Artist House 45, and theorised this as critical spatial practice.[ii] Yet there are other issues that prompted the work, for example, the UK housing crisis. This book responds to these multiple starting points, individual and social, but also suggesting possible future trajectories. For me, reading Jon’s thesis the first time around it seemed important to publish such a multifaceted work in a manner that fully reflected its open ethos. This book does just that; building on the participatory form of the research and practice, and involving as many of those who were part of his residency as possible. The publication is collaborative, right through to the structure and design, including how the words and images speak to each other.

When I first engaged with Jon’s practice, I was starting to think about Donald Winnicott’s notion of ‘living with’ and all the joys and tensions of co-habitation. I was living with my Mum at the time, and getting used to a range of different daily rituals around the home, some of which felt especially strange, as we were in the second COVID-19 lockdown, and grieving the loss of my Dad. Mourning as I came to experience it, is a discontinuous process, as are acts of domestic labour, reproduction, and caring; continuous as the lives they support, discontinuous as the ways in which they are always about-to-be-interrupted, because they are not considered important enough to command sufficient space and time.

Discontinuous thinking takes place in fragments. In what he calls ‘figures’ in a Lover’s Discourse, and then later ‘traits’ in How to Live Together, Roland Barthes explores ways of co-existing or living together in fragments. How to Live Together, comprising translated transcripts of his lecture course at the Collège de France, is itself configured as a series of discontinuous units, what Barthes calls traits: ‘clearly bound up with a certain politics …’. This he describes as ‘A politics that seeks to deconstruct metalanguage,’[iii] and one which allows him to concentrate on indirect relations, to deviate from following a path, and to ‘present … findings as we go along.’ [iv]

Presenting findings as we go along …

Today, as I read Jon’s work again, this time with all the findings of his residency presented with other voices and reconfigured into this polyvocal publication, I am less caught up with the fragmentation of living-with, in all its modes and moods of melancholy, and more able to enjoy the creative possibilities and insights gained by sharing fragments of his patient open practice. Winnicott is, as far as I know, the one who came up with the concept of ‘living with.’ It emerged connected to his work on holding and on the caring environment that a parent (specifically in his work – a mother) creates for a child, and the supportive environment an analyst makes for an analysand.[v] For Winnicott, a holding environment insulates a baby or analysand from stress, but also allows moments of frustration to enter. Gradually adjusting to the withdrawal of care as an immediate response to need, a holding environment is what allows the baby or analysand to develop creatively and to become self-sustaining. This environment, or what Winnicott also calls a ‘transitional space’ between parent and child or analyst and analysand, exists as a resting place for the individual engaged in keeping inner and outer reality separate yet interrelated.[vi] In Winnicott’s work transitional space is retained in later life in the area of intense experiencing that belongs to the arts, to religion, to imaginative living and to creative scientific work, providing relief from the strain of relating inner and outer reality. He discusses how cultural experience is located in the ‘potential space’ between ‘the individual and the environment (originally the object)’:[vii]

“The term ‘living with’ implies object relationships, and the emergence of the infant from the state of being merged with the mother, or his perception of objects as external to the self.” [viii]

For Winnicott, conceptualising the experience of ‘living with’ intimately connects to the caring practice of holding:

“The term ‘holding’… denote[s] not only the actual physical holding of the infant, but also the total environmental provision prior to the concept of living with.”[ix]

[i] Jonathan Orlek, ‘Moving in and Out, or Staying in Bed: Using Multiple Ethnographic Positions and Methods to tudy Artist-led Housing as a Critical Spatial Practice,’ (Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield, 2021).

[ii] Jane Rendell, Art and Architecture: A Place Between, (London: IB Tauris, 2006).

[iii] Roland Barthes, How to Live Together: Novelistic Simulations of some Everyday Spaces, Notes for a Lecture course and seminar at the Collège de France (1976-7) translated by Kate Briggs, (Colombia University Press, [2002] 2013), p. 20.

[iv] Barthes, How to Live Together, p. 133.

[v] D. W. Winnicott, ‘The Theory of the Parent-Infant Relationship,’ The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment: Studies in the Theory of Emotional Development, The International Psycho-Analytical Library, (London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis, [1960] 1965), pp. 37-55.

[vi] D. W. Winnicott, ‘Transitional Objects and Transitional Phenomena – A Study of the First Not-Me Possession’, International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, v. 34 (1953), 89–97.

[vii] D. W. Winnicott, ‘The Location of Cultural Experience’, The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, v. 48, (1967) pp. 368–72, 317.

[viii] Winnicott, ‘The Theory of the Parent-Infant Relationship,’ pp. 43-4.

[ix] Winnicott, ‘The Theory of the Parent-Infant Relationship,’ pp. 43-4.

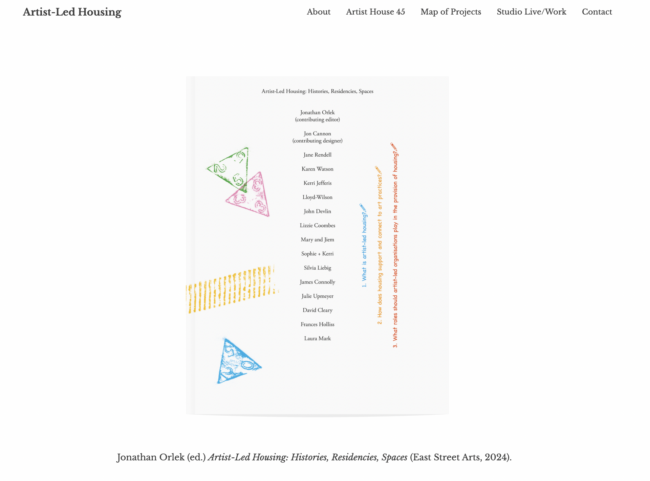

ARTIST-LED HOUSING: HISTORIES, RESIDENCIES, SPACES by Various Artists