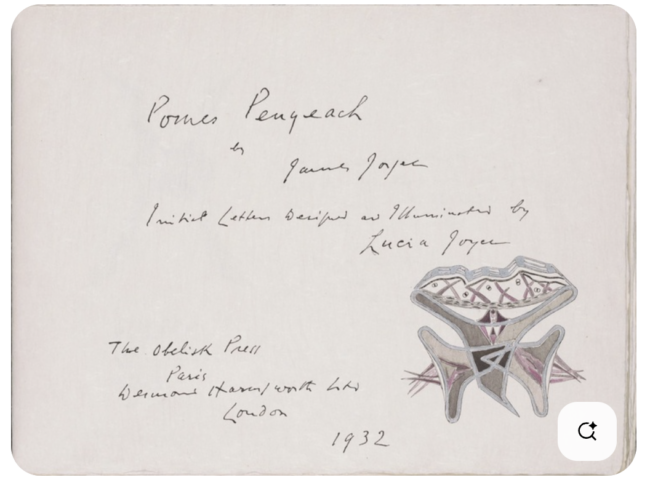

In re-reading Jennifer Bloomer’s Architecture and the Text: the (S)crypts of Joyce and Piranesi[i] through an essay I wrote as student in 1994 called ‘Bloomer’s Babble,’[ii] I discover so many ways in which Architecture and the Text is related not only to that essay and my own life then, but also to feminism’s re-writing of architectural theory in the 1990s. At that time Bloomer’s blend of theorising, historical reflection, textual practice, and her uniquely autobiographical voice, offered an alternative direction for many feminist architectural writers of my generation. Revisiting my earlier reading of Bloomer turns out to have been a journey of rediscovery and repositioning. I find now that some things are still there, but in a different place; and others I thought I had lost long ago reappear, somewhere else; while new attractions beckoning for the first time. My rereading refigures, as a ‘site-writing,’[iii] the ‘Three-Plus-One’ spatial structure that Bloomer’s book adopts and adapts from her reading of James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake (1939). For reasons that I only reveal at the end, I decided to take the 13 (One-Plus-Three) poems collected in James Joyce’s Pomes Penyeach (1932),[iv] and to supplement these with 13 ‘plus-one’[v] fragments of my own. Joyce’s Pomes Penyeach consists of 13 poems, each one composed on a piece of thick cream paper, folded and then bound together and held in an orange box. Each poem presents a ‘threesome;’[vi] on opening the folded paper the reader encounters a poem typed on a sheet of transculent tissue veiling two further elements just visible beneath – the same poem this time handwritten by Joyce accompanied by a coloured lettrine designed by his daughter Lucia Joyce. In what follows I reconfigure this arrangement as 13 (Three-Plus-One)s – each ‘threesome’ opens with the title and first line of one of the 13 poems, followed by an image of the full handwritten poem and its adjacent lettrine positioned beneath. On the opposite page, I write a supplement. And each time, I take, as the starting point of my own text, the first letter of his first line, that she, his daughter, drew.

Published in a special issue of The Journal of Architecture, Jennifer Bloomer: A Revisitation, edited by Emma Cheatle and Helene Frichot, v. 28, n. 6, (2023).

https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2023.2272434

[i] Jennifer Bloomer, Architecture and the Text: the (S)crypts of Joyce and Piranesi (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1993).

[ii] Jane Rendell, ‘Bloomer’s Babble,’ MA Architectural History dissertation, UCL (May 1994).

[iii] See Jane Rendell, Site-Writing: The Architecture of Art Criticism, (London: IB Tauris, 2010). See also Jane Rendell, ‘Sites, Situations, and other kinds of Situatedness’, Bryony Roberts (ed), Expanded Modes of Practice, Special Issue of Log 48, (Winter/Spring 2020), pp. 27–38 and Jane Rendell, ‘Marginal Modes: Positions of Architecture Writing,’ Architectural Review (August 2020)

https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/marginal-modes-positions-of-architecture-writing

[iv] James Joyce, Pomes Penyeach, initial letters designed and illuminated by Lucia Joyce, (Paris: Obelisk Press/London: Desmond Harmsworth, 1932).

[v] Bloomer, Architecture and the Text, p. 4

[vi] Bloomer, Architecture and the Text, p. 4